A giant Shinsekai Billiken

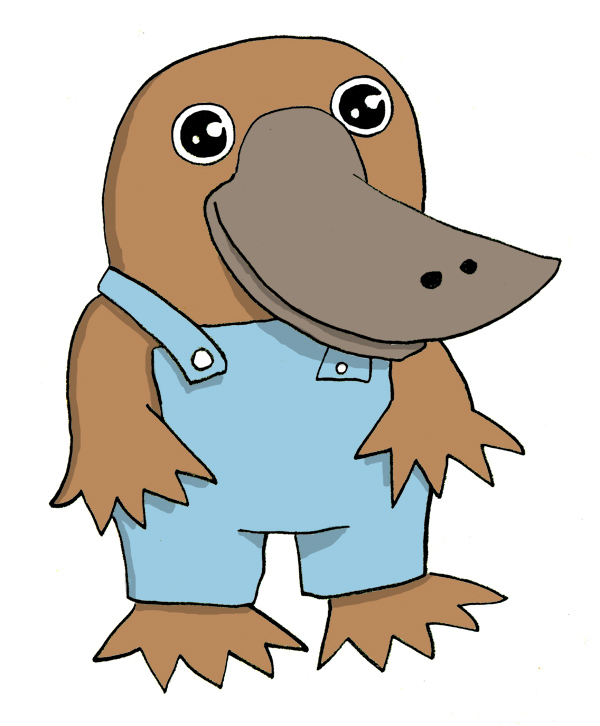

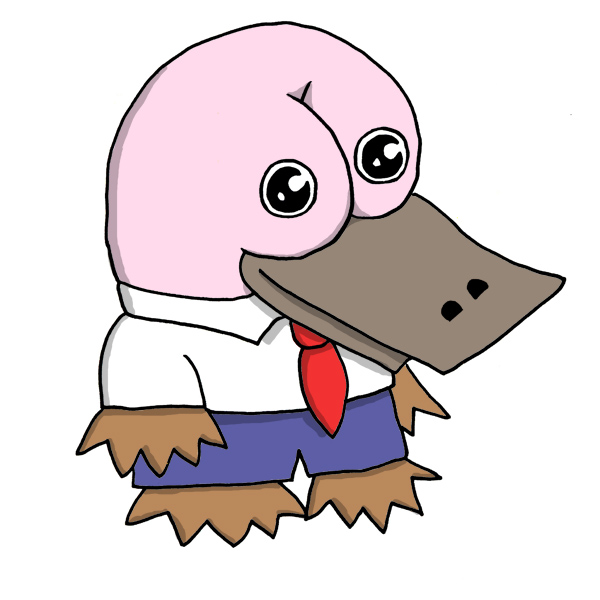

If you take a stroll through Osaka’s retro mecca, Shinsekai, you are sure to notice dozens of images and effigies of a curious character known as the Billiken. A serenely smiling, Buddha-like figure, the Billiken looks a bit like the actor, Wallace Shawn, from The Princess Bride. Each statue of the cherubic character sits flat on a plinth with the soles of his feet facing outward. It is considered lucky to tickle these oversized feet, and the denizens of Shinsekai can often be spotted doing this. When I spoke to some tourists visiting Shinsekai from other parts of Japan, they told me they had assumed that the Billiken was a religious symbol. He is indeed called “the god of things as they ought to be”, but his origins are in fact as a mascot character, and his story begins in the U.S. A.

Billiken bench in Shinsekai

In 1908 a mysterious rotund figure appeared to Missouri art teacher, Florence Pretz, in a dream. She drew the character and named it the Billiken. Apparently the name comes from the 1896 poem, “Mr. Moon: A Song of the Little People” by the Canadian poet, Bliss Carman.

O Mr. Moon,

We’re all here!

Honey-bug, Thistledrift,

White-imp, Weird,

Wryface, Billiken,

Quidnunc, Queered;

We’re all here,

And the coast is clear!

Moon, Mr. Moon,

When you comin’ down?

Pretz patented the design (the first ever patented god) and sold it to The Billiken Company of Chicago. Soon they were mass-producing all sorts of Billiken merchandise—dolls, statuettes, marshmallows, pickle forks, hatpins, watchfobs, and incense burners to name but a few items. The Billiken became an overnight hit and even inspired songs, such as “Billiken Man” by Blanche Ring (1909).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vgIKrEd4tBg

Such fads were commonplace in the early 20th Century. Kewpie, a baby cupid character designed by cartoonist Rose O’Neill and which also enjoys enduring popularity in Japan, appeared the following year and was the subject of a similar craze.

The Billiken was seen by many as a tribute to then-president, William (Bill) Taft. His predecessor, Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt, had inspired the hugely popular teddy bear toys, and the mass-markerting of the Billiken was perhaps an attempt to replicate the teddy bear’s enormous success. There is even a terrifying hybrid of the two characters, called the Teddy Billiken.

The sinister Teddy Billiken

At the height of his fame, the Billiken became the official mascot of St. Louis University, due to his resemblance to their football coach of 1910-11, the beatific, grinning John Bender (not to be confused with John Bender, Judd Nelson’s brooding delinquent character from 1985’s “The Breakfast Club”, who is anything but beatific). The Billiken remains the university’s mascot to this day, and even made the news last year, when a new design of the character provoked a horrified reaction from the University’s students.

Even welcome in the shadowy world of freemasonry, the Billiken became the official mascot of the secretive Royal Order of Jesters, an elite Shriner group dedicated to the celebration of mirth.

Alas, within a couple of years, the initial American Billiken boom was over, but his legend lived on in Alaska, where for decades Eskimos could be found selling tiny ivory Billiken figures carved from walrus tusks.

Yakitori restaurant clown Billiken

Meanwhile, the Billiken took Japan by storm. Looking like a long lost cousin of Japan’s Seven Lucky Gods, the pudgy deity was a natural fit for the country. Florence Pretz claimed she had been “dreaming of all things Japanese” when she first conceived of him. She even speculated that she had been Japanese in a past life, and was photographed wearing a kimono for the Chicago Daily Tribune in 1908.

The Japanese were so accepting of “the god of things as they ought to be” that Billiken statues were enshrined throughout the country. Prewar Billikens can still be found in Kobe shrines to this day. This is like having a stained glass window of Hello Kitty in a Catholic church.

Elephantine rooftop Billiken

Japan’s best-known Billiken was enshrined in a Shinsekai funfair, Luna Park, in 1912. Since 1980, a replica of the famous Luna Park Billiken has been on display in Shinsekai’s prominent Tsutenkaku tower, and the porky fellow has been indelibly associated with the place ever since. That particular Billiken even went on to inspire a light-hearted 1996 comedy film, Billiken (directed by Junji Sakamoto), in which the titular mascot uses his power of luck to help the Shinsekai tourist board stop the demolition of Tsutenkaku tower. Today, the movie can be found on Japanese Netflix.

Billiken (1996)

And so it is that the streets of Shinsekai came to be crowded with statues and pictures of “the god of things as they should be”. While there, I bought myself a golden Billiken statuette because I could use some good luck, and it now sits proudly on my coffee table. Buying a Billiken is thought to bring good fortune, but it is considered luckier to be given one, and luckiest of all if you steal it.

Triumphant Billiken