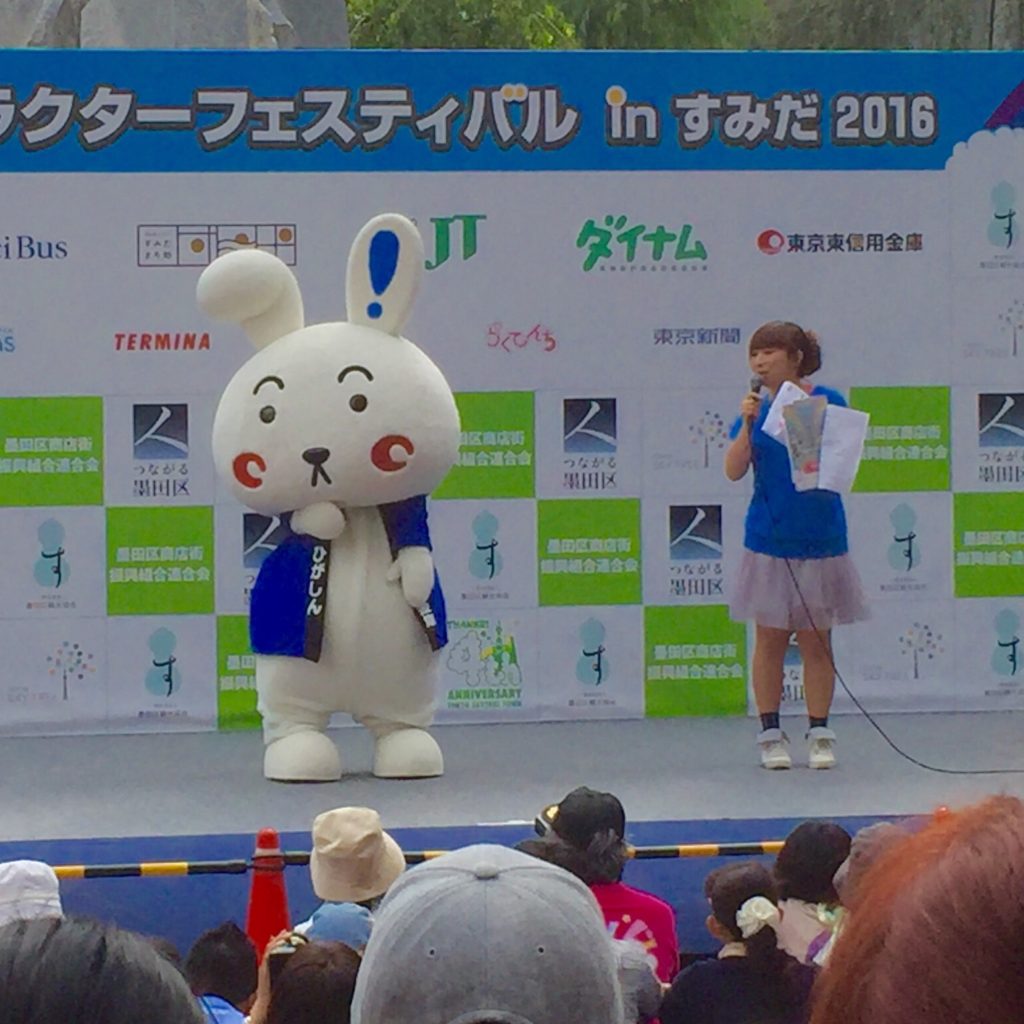

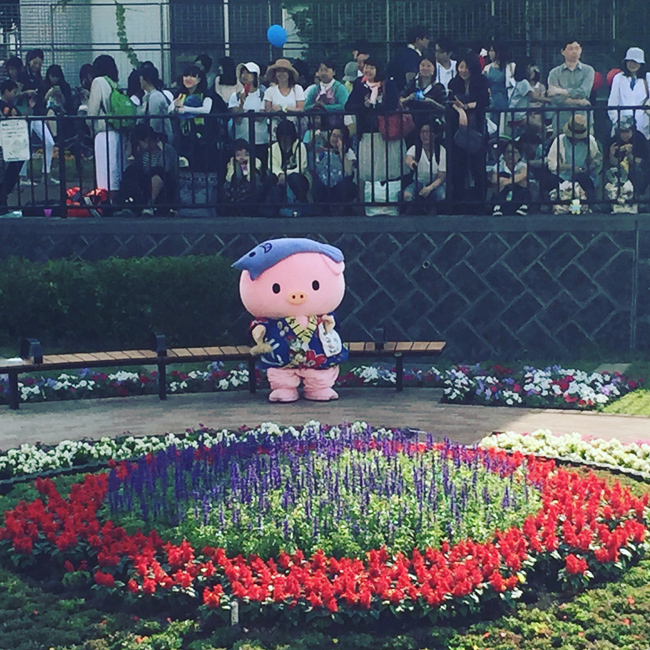

Last weekend was the annual Gotouchi-chara Festival in Sumida, Tokyo. One hundred different regional mascots gathered at three stages and a park near the base of Japan’s tallest structure, the Sky Tree. Here are some pictures from the first day of the event.

Tosakenpi, winking. Tosakenpi is a Tosa dog from Harimaya Bridge in Kochi. He likes sweet potato “kenpi” snacks.

2012 Yuruchara Grand Prix winner, Bari-san, is a giant baby chicken and the mascot of Imabari City in Ehime. Ehime is famous for chicken dishes, so he should consider relocating.

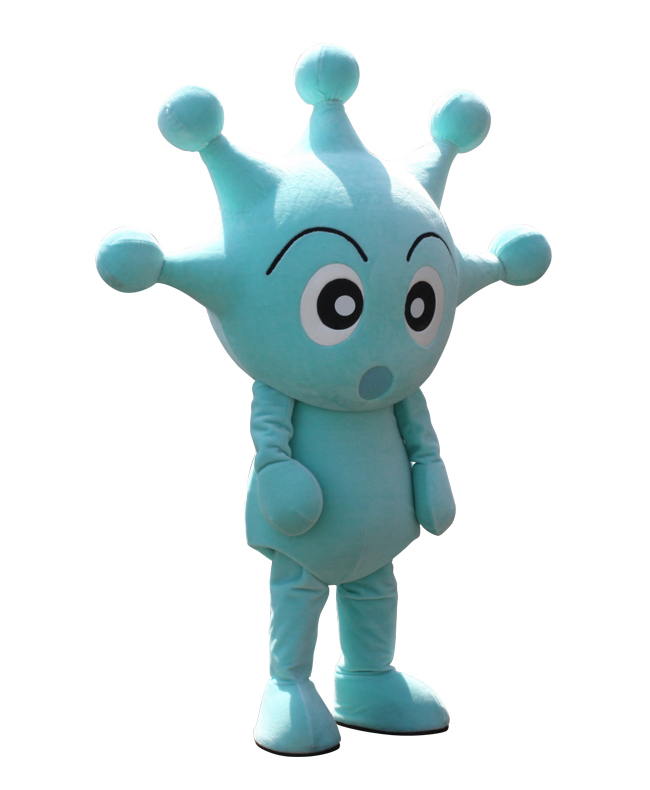

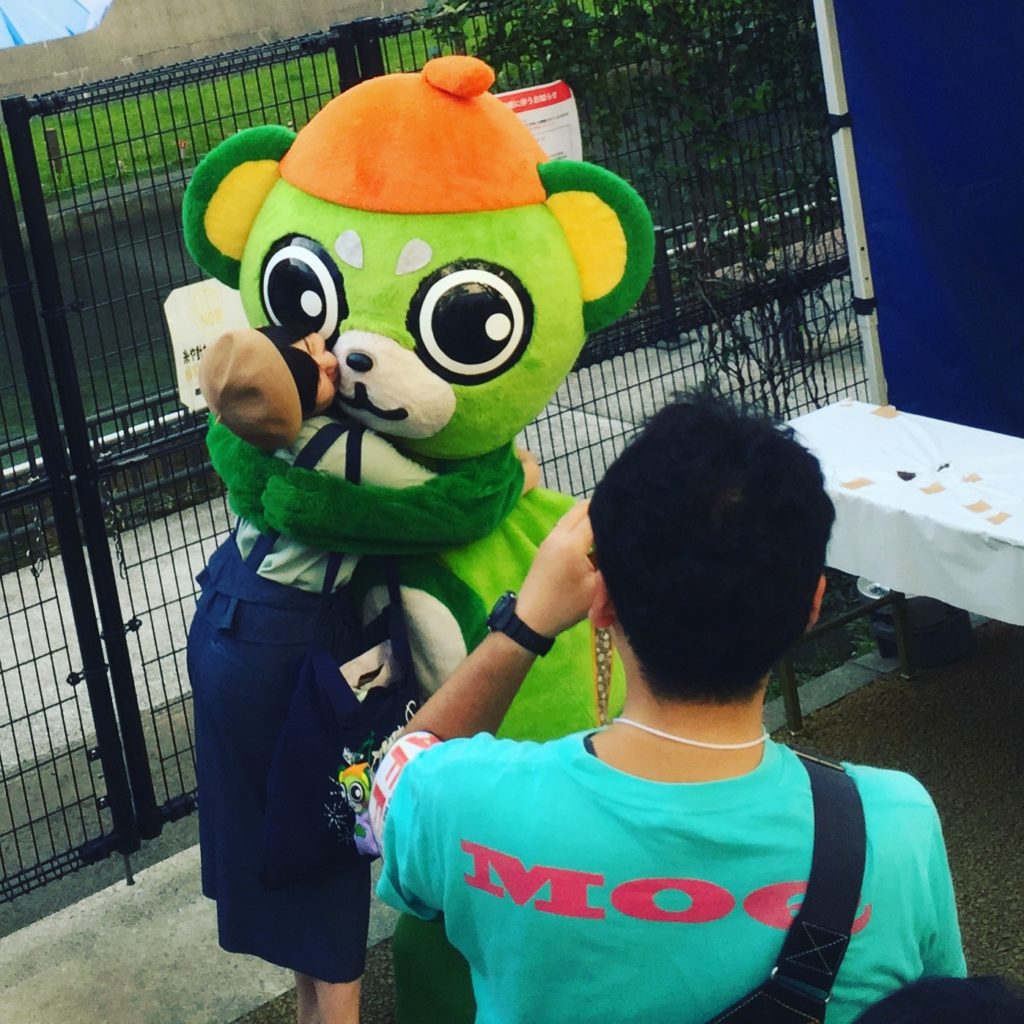

Cable internet company JCOM’s bouncy mascot ZAQ meets noodle-brained Udon Nou from Kagawa Prefecture.

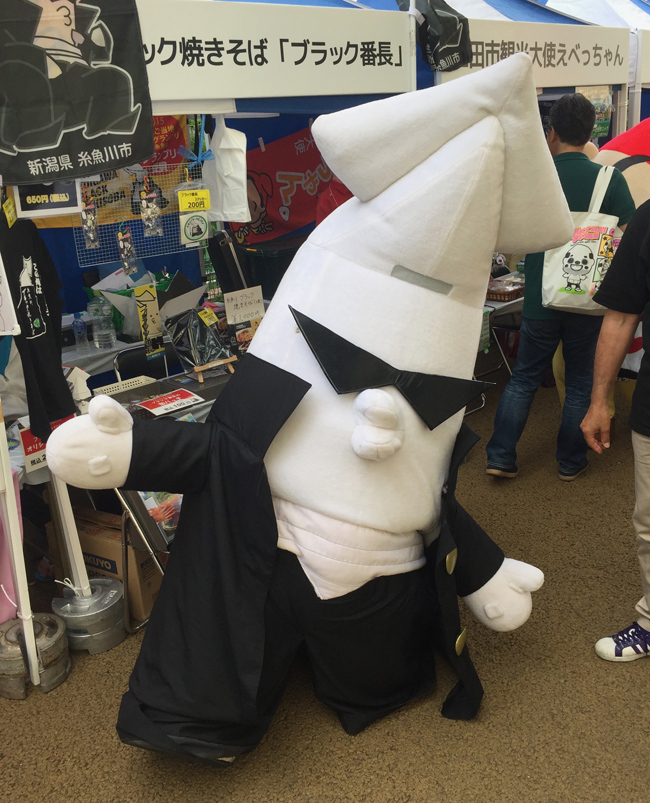

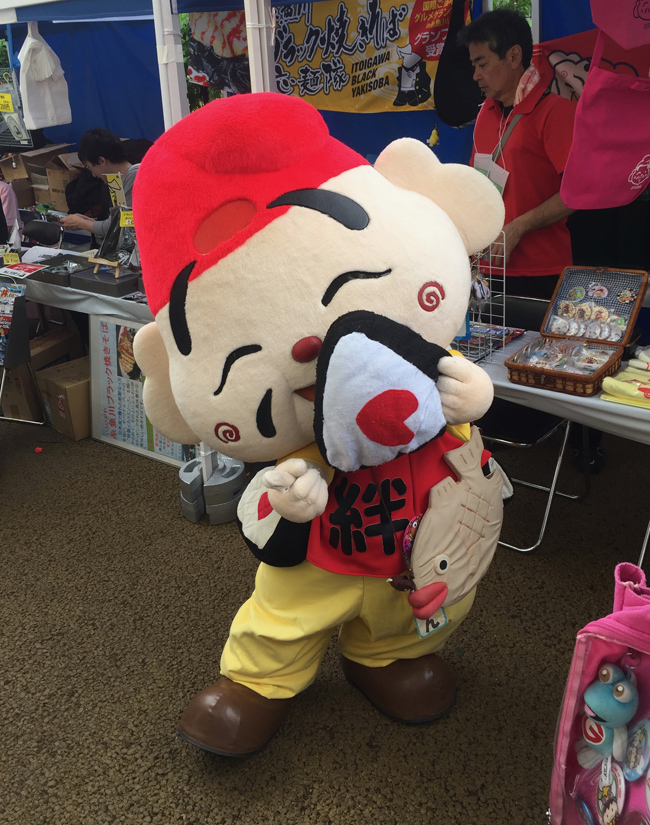

The slick and streetwise squid, Black Bancho, is the mascot for Itoigawa City in Niigata.

Konyudo-Kun, the mascot for Mie Prefecture’s Yokkaichi City, pulls out his tongue.

Yoichi-kun, mascot of Otawara City, Tochigi, sells his wares.

Chiryuppi of Chiryu City, Aichi.

Mikke-Chan is a ballet dancing calico cat and the mascot for a shopping street in Hirakata City, Osaka.

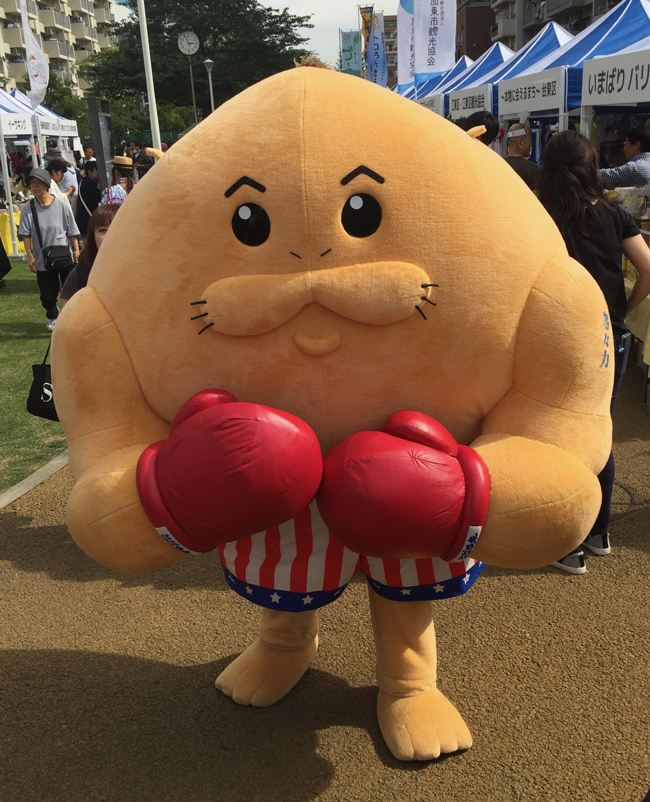

Todorocky is the mascot for Todoroki, in Tokyo’s Setagaya Ward. He’s a musclebound sea lion who likes boxing and sweet buns.

Chiba mascot, CHI-BA+KUN, takes his shape from the outline of the prefecture.

The ubiquitous Kumamon, of Kumamoto Prefecture, busts some moves on the stage.

Sugamon the duck is a hit with the older women- he’s the mascot for Sugamo shopping district, the fashion Mecca for Tokyo’s elderly ladies.

Zombear entertains the crowd with a string of intestines.

2UYakisoban, a superhero with a bowl of yakisoba noodle soup for a head, hails from Kuroishi City in Aomori.

Tochigi mascot, Tochi-suke, is a warehouse fairy.

Melon-haired, onsen-eyebrowed Kikuchi-kun is the unauthorised mascot for Kikuchi, Kumamoto. He loves his town but scares local children.

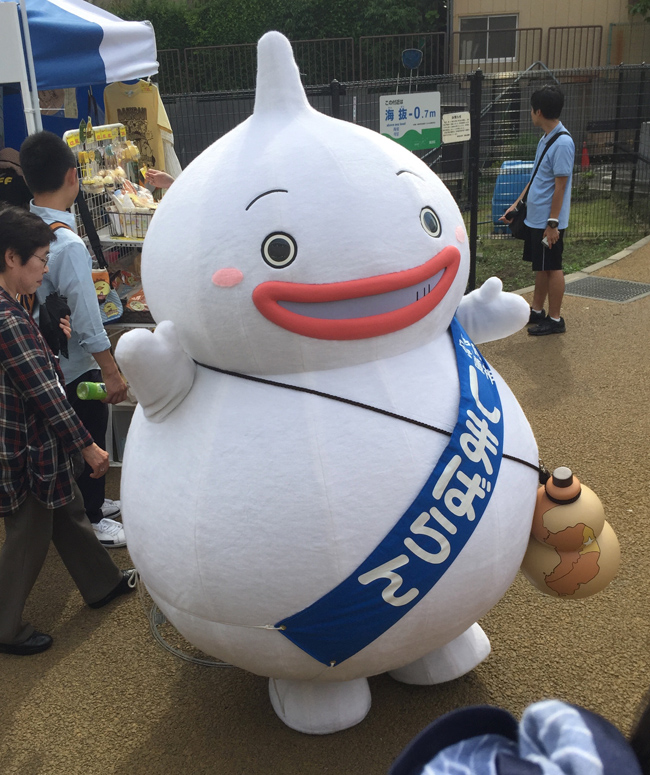

The adorable Ebecchan is the sightseeing ambassador of Sanda City in Hyogo. His special skill is catching rice balls.

Hamamatsu’s Ieyasu-kun was the winner of the 2015 Yuruchara Grand Prix.

Shimabaran is the guardian deity of Shimabara, Nagasaki. This character was designed by the creator of Yokai Watch, Noriyuki Konishi.

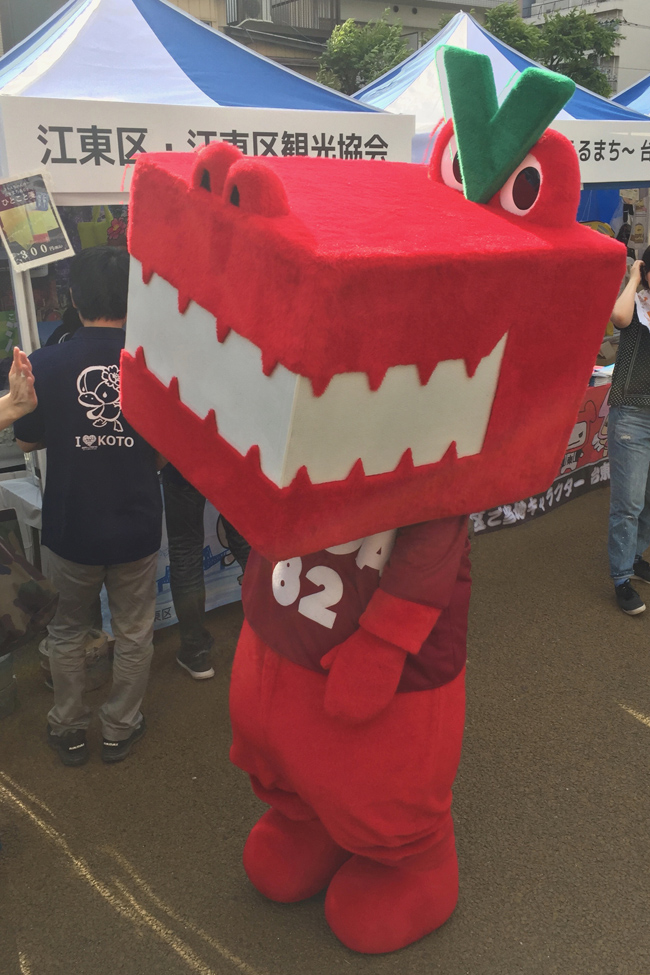

Sumidile is the mascot of Fugador Sumida, the local futsal team.

Big-eared Hanipon (left) is the mascot of Honjo City in Saitama and came second in last year’s Yuruchara Grand Prix. Here he meets the regal Isa King (right) who hails from Isa City, Kagoshima.

Kiriko-chan looks like the fog that rolls in from the sea in her hometown of Miyoshi City, Hiroshima.

Tokoron, of Tokorozawa in Saitama, doesn’t usually have those eyebrows.

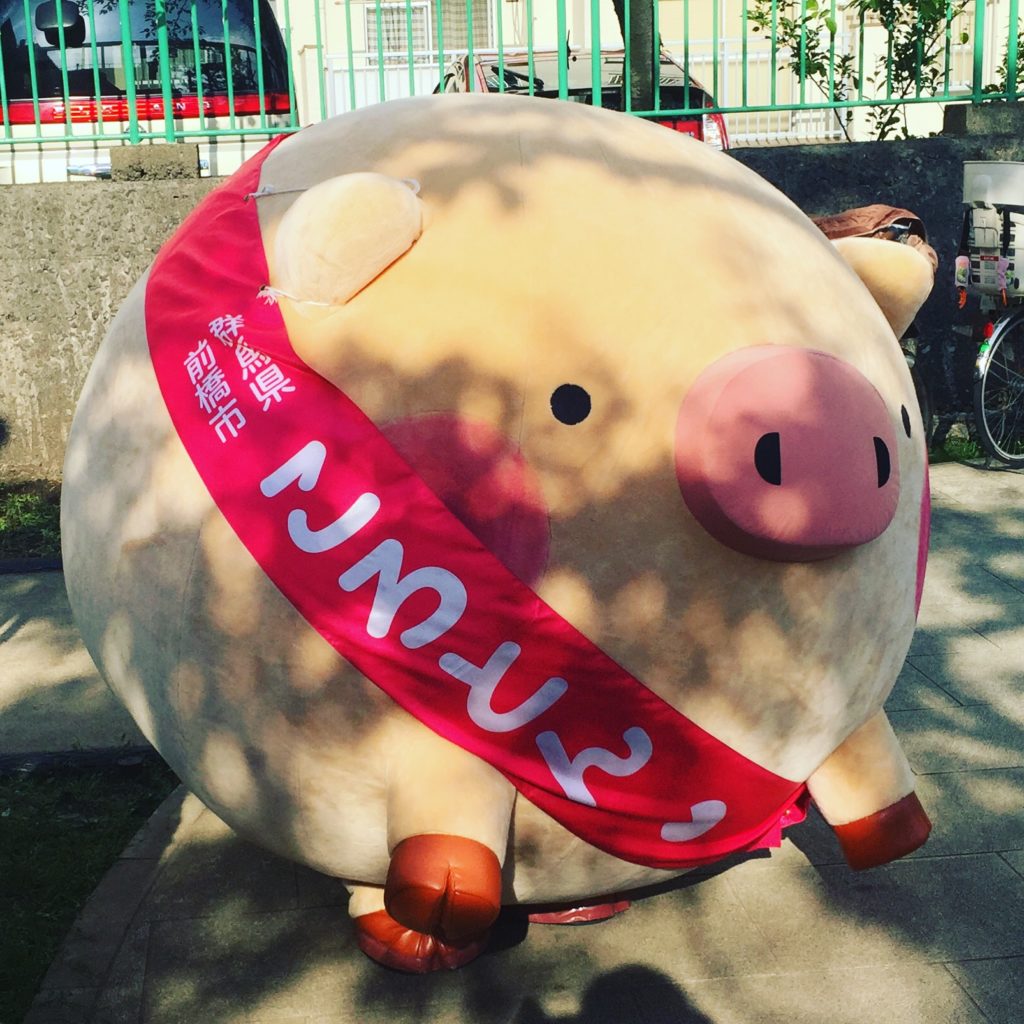

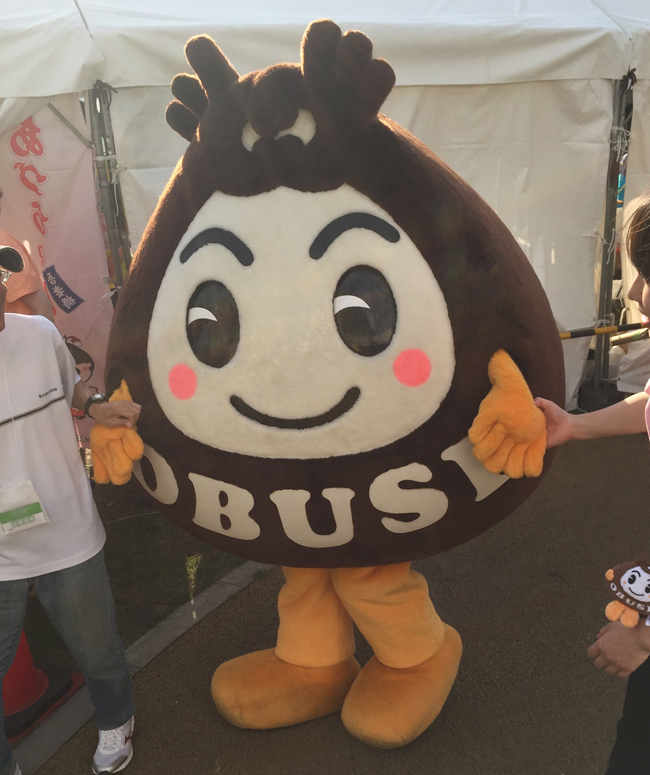

Obuse Kuri-chan of Obuse, Nagano is surely the world’s biggest chestnut.

Hokkaido’s Jingisukan No Jinkun is a sheep named after a grilled mutton dish. No wonder he’s brandishing a sword.