Most Japanese towns and cities have their own, government-approved “gotouchi-chara” mascots, who help promote tourism and liven up local festivals; but renegade, “unofficial” mascots are just as likely to win the public’s favour. The official mascots are usually wholesome and squeaky-clean, so they tend to be upstaged at events by their unsanctioned counterparts, with their garish designs, and anarchic, outlandish behaviour. Typically, an unofficial mascot does not put forward an image of their hometown that the local government wants to project. But, much to the chagrin of local politicians, the unapproved mascots often turn out to be more successful than the approved ones.

Funassyi vs. Funaemon

Funassyi (left) and Funaemon

Everyone’s favourite hyperactive pear, Funassyi, was conceived by a resident of Funabashi, Chiba, as a potential mascot for the city. But when its creator offered Funassyi to the town, they turned him away. Instead, a couple of years later, they came up with the spectacularly dull Funaemon, an Edo-era merchant who looks like a bland accountant from a 70s British sitcom. Whichever civil servant made that disastrous decision must feel as remorseful as those publishers who rejected the manuscript for Harry Potter.

Funassyi went on to become the country’s most popular mascot, raking in billions of yen through merchandise for its creator, who is now laughing all the way to the bank. While Funassyi could have generated a fortune in revenue for Funabashi City, it seems unlikely that boring old Funaemon will enjoy the same success.

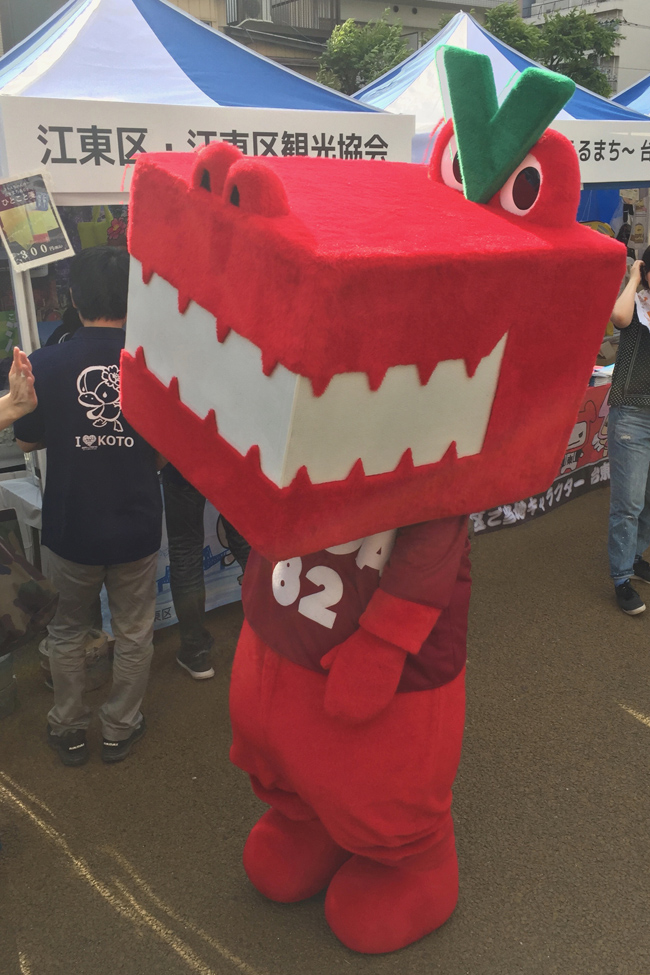

Korou-kun vs. Kikuchi-kun

Korou-kun (left) and Kikuchi-kun

The official mascot of Kumamoto’s Kikuchi City is a cute soldier named Korou-kun. He’s a perfectly serviceable mascot, but looks sadly unremarkable when standing next to his unofficial mascot rival, Kikuchi-kun.

The unique Kikuchi-kun is a Frankenstein’s monster cobbled together from various points of pride from Kikuchi City (a locally-grown melon for a head, hot springs for eyebrows, a dairy cow’s legs, etc.) Although initially unpopular (he made children cry at his first public appearance) Kikuchi-kun has cultivated a cult following for his dry, deadpan comments.

Regardless of who proves to be more popular, both characters will have to endure living in the shadow of Kumamoto’s almighty Kumamon.

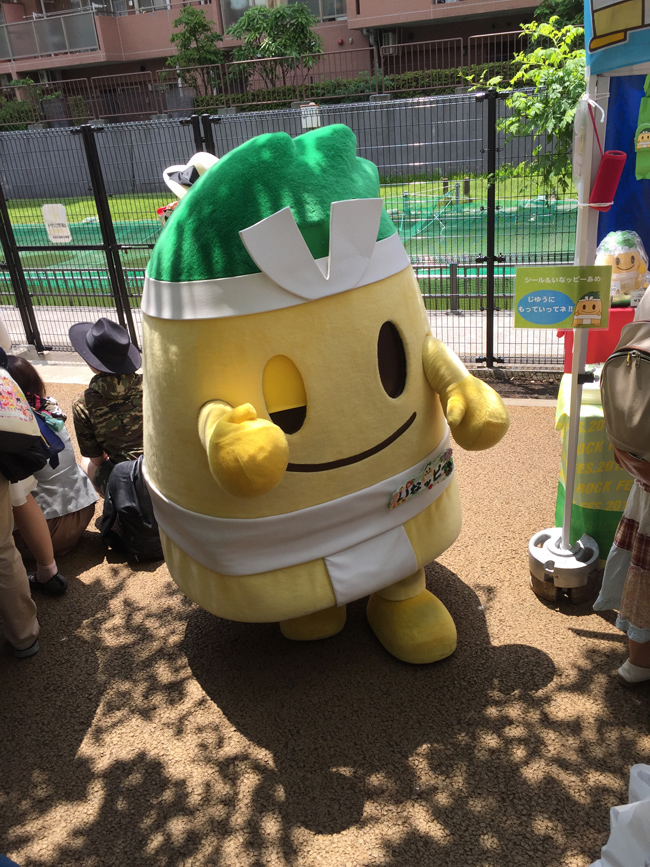

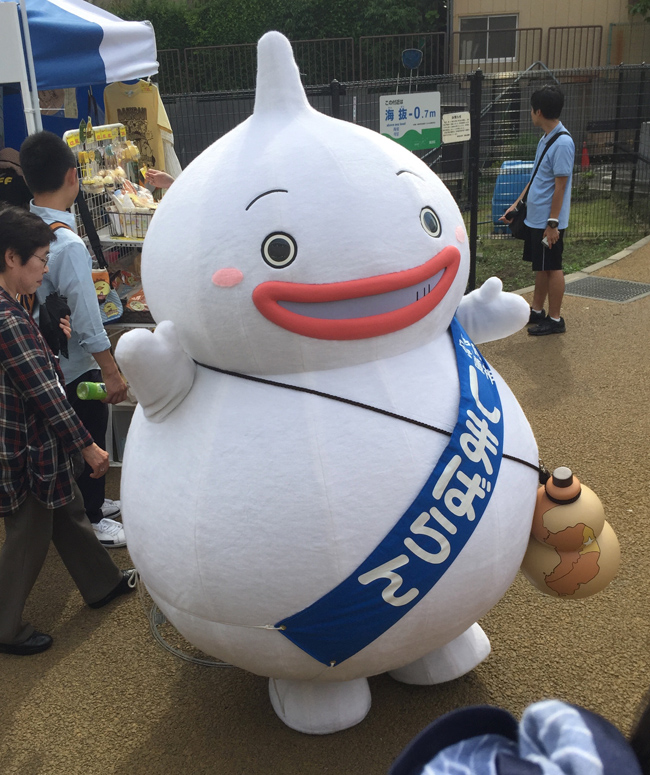

Hustle Komon vs. Nebaaru-kun

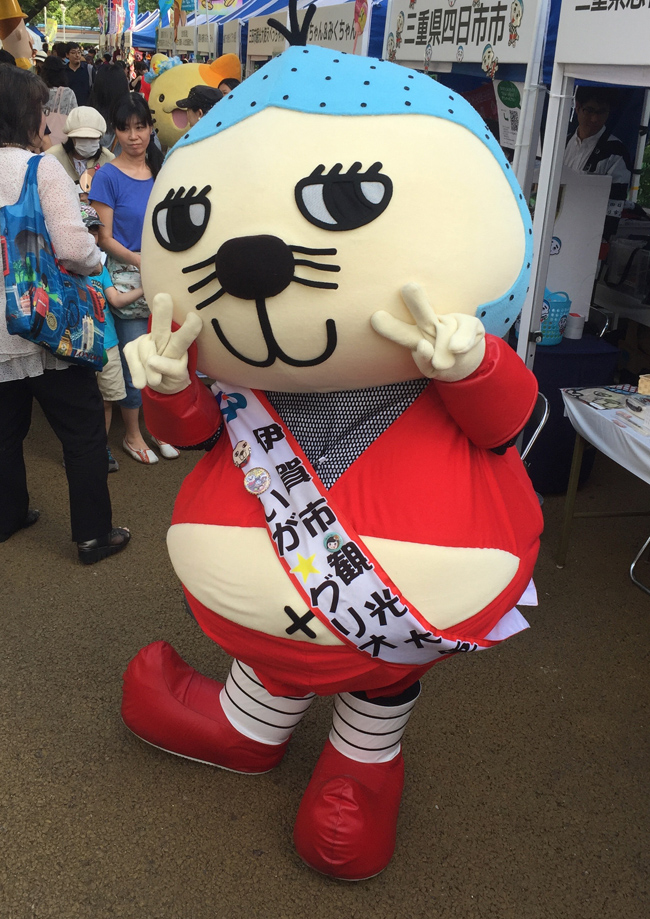

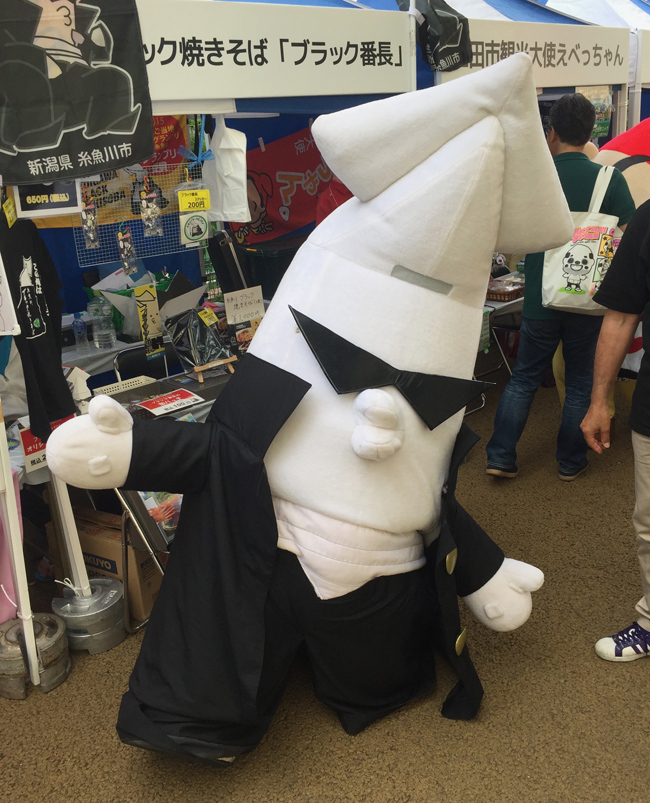

Hustle Komon (left) and Nebaaru-kun

Ibaraki Prefecture’s official mascot is an old hustler named Hustle Komon, based on a character from the long-running Ibaraki-set period drama, Mito Komon. He faces competition from a lovable natto fairy named Nebaaru-kun. Natto is a healthy but foul-smelling food made from fermented soybeans, and originates from Ibaraki. Imitating the slimy beans, Nebaaru-kun stretches high in the air—an impressive spectacle. How can an old geezer compete with that?

Take note, mascot designers: human mascots are never popular.

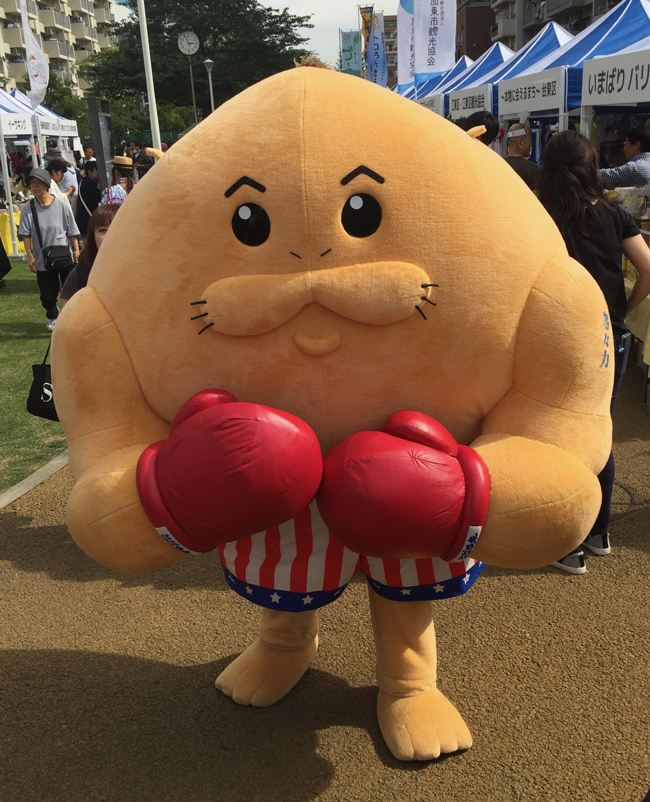

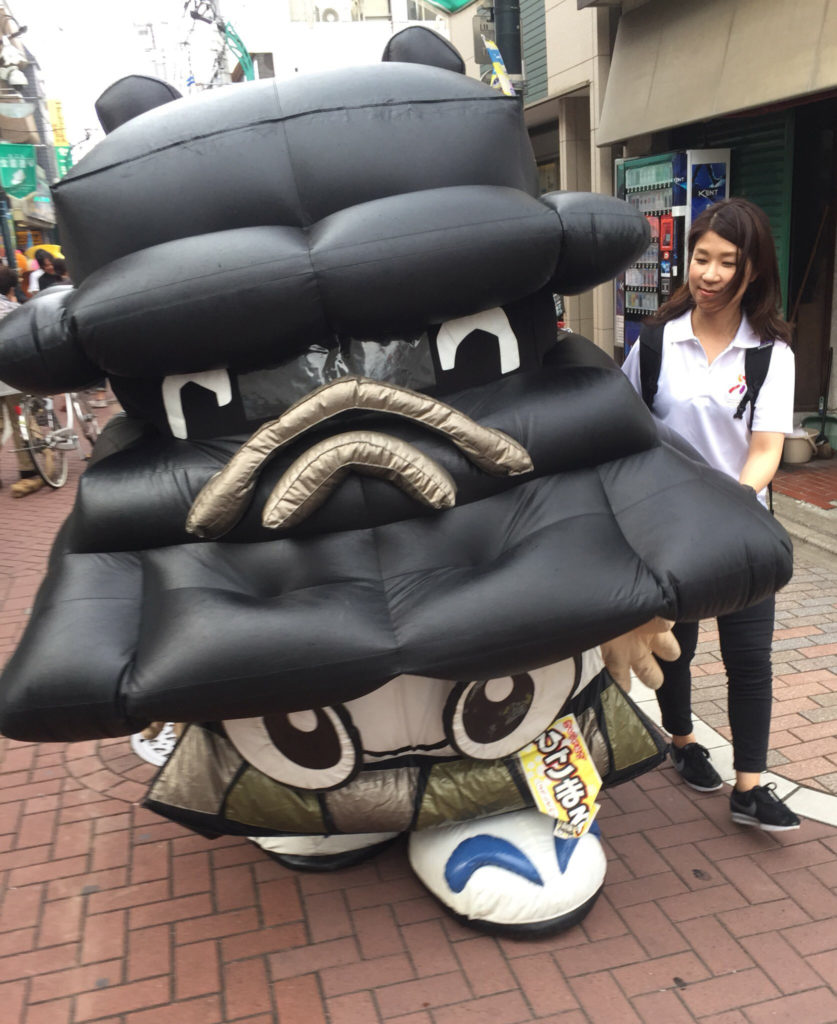

Amakko-chan vs. Chicchai Ossan

I spoke too soon. One human mascot who is very popular is Chicchai Ossan, unofficial mascot of Amagasaki City, Hyogo. A balding, unshaven, middle-aged slob in a singlet, Chicchai Ossan is very relatable, thanks to his myriad imperfections.

These same imperfections no doubt led Amagaski’s government officials to look elsewhere for their official mascot. They recently chose Amakko-chan, a heart-headed girl who had been the city’s bus mascot until the service was privatized. Amakko-chan is charming, but she will have her work cut out if she wants to match Chicchai Ossan’s popularity.

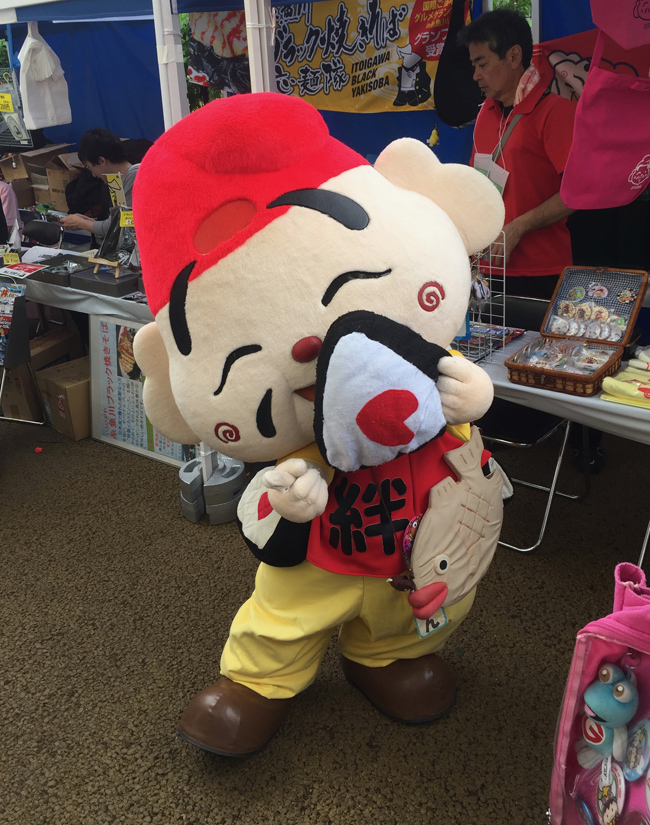

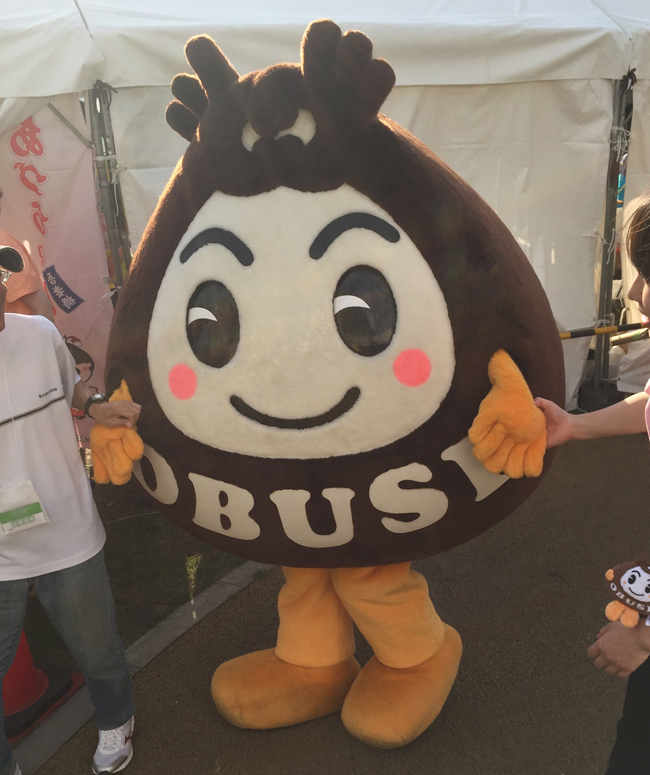

Mayumaro vs. Warabi Maiko-chan

The beautiful historic prefecture of Kyoto has a surprisingly bizarre official mascot—a giant, 2000-year-old, waddling silkworm cocoon named Mayumaro. Somehow, his illegitimate rival is even weirder. Warabi Maiko-chan is a combination of a mochi dumpling and an apprentice geisha. What’s more, the costume is transparent, so you can see the performer inside.

Luckily for all these characters, the healthy competition between official and unofficial mascots never turns nasty. It is not in the nature of yuru-chara to be vindictive, so they all seem to get along just fine.

Tom is the American embassy’s mascot. He’s a jellybean because the countless flavours of jellybeans represent the USA’s diversity.

Tom is the American embassy’s mascot. He’s a jellybean because the countless flavours of jellybeans represent the USA’s diversity. The Finnish embassy’s mascot appears in anime videos and has 130,000 followers on Twitter. Apparently, like many westerners drawn to Japan, he’s into cosplay- he’s always wearing a lion costume.

The Finnish embassy’s mascot appears in anime videos and has 130,000 followers on Twitter. Apparently, like many westerners drawn to Japan, he’s into cosplay- he’s always wearing a lion costume. The Israeli embassy’s adorable mascot, Shaloum-chan, is a cockatoo extending an olive branch. His name is a combination of the Israeli word for peace, “shalom”, and the Japanese word for cockatoo, “oum.” The creator clearly knows how the Japanese do mascots.

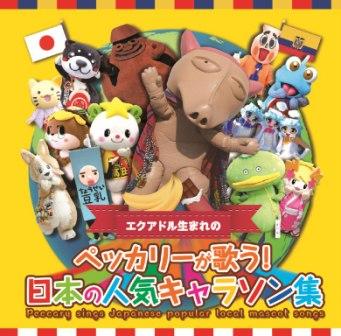

The Israeli embassy’s adorable mascot, Shaloum-chan, is a cockatoo extending an olive branch. His name is a combination of the Israeli word for peace, “shalom”, and the Japanese word for cockatoo, “oum.” The creator clearly knows how the Japanese do mascots. Ecuador’s odd-looking Peccary is based on a clay figure in the Bizen Latin American Museum in Bizen, Okayama Prefecture, a city for which he also acts as a mascot. Peccary is quite the crooner, and has released a CD of covers of other yuru-chara’s songs, “Peccary Sings Japanese Popular Local Mascot Songs”.

Ecuador’s odd-looking Peccary is based on a clay figure in the Bizen Latin American Museum in Bizen, Okayama Prefecture, a city for which he also acts as a mascot. Peccary is quite the crooner, and has released a CD of covers of other yuru-chara’s songs, “Peccary Sings Japanese Popular Local Mascot Songs”.